With beautiful rolling hills and verdant valleys, redwoods and oak trees, streams and hot springs, and proximity to both mountains and the Pacific Ocean, Gilroy has been an essential crossroads in California for thousands of years.

The oral history of native Americans tells us that Chicatac-Adams State Park was a spiritual place that attracted Native Americans from as far as Oregon and the Sierra Nevada to convene, pray and dance. Gilroy also factors prominently as a crossroads in early Spanish California and European settlers’ history.

Today, Gilroy remains an important “hub” and a popular destination for travelers on their way to Monterey, Santa Cruz, San Jose, San Francisco, and Pinnacles National Park.

Gilroy City Historian Toby A. Echelberry has written this in-depth article so we can all learn more about Gilroy’s role in California’s past—and how the roads we traverse today are steeped in important (and fascinating) history.

Passing Through Gilroy: Famous Expeditions and Trails Crossing through Gilroy’s Past by Toby A. Echelberry, Gilroy City Historian

Gilroy is nestled in South Santa Clara County. The center of town sits at the crossroads of U.S. Highway 101 and California State Route 152 and soon will be a future stop for high-speed rail. In its history, Gilroy has had many other famous expeditions, trails, roads, and railways pass through this area as well. Here is some of the legacy of current and past pathways that ventured through this area and shaped local history.

Indigenous Trails

The Amah Mutsun Tribe had an extensive history of communal activity, shared cultural understanding, and collective rituals and beliefs. The Amah Mutsun occupied the San Juan Valley for thousands of years before the Spanish arrived in the late 1700s.

For 1700 to 2700 years, the Amah Mutsun community made this part of California their home. The Amah Mutsun was originally made up of 20 to 30 contiguous villages stretched across the Pajaro River Basin and surrounding region. The Amah Mutsun community had been drawn to the area due to the proximity of the Pajaro and San Benito rivers and the abundance of water and fish. The various Mutsun villages were united due to their shared cultural and tribal traditions. They shared, traded, and comingled together, with mutual religious practices, ceremonial dress, craftmanship, methods of fishing and hunting, and tools.

The Mutsun community was a portion of the larger community of the Costanoan/Ohlone family; the geographical area set them apart from the larger community. The Mutsun language was one of the eight Costanoan/Ohlone languages and was one of the first American Indian languages studied in North America. In the nearby Mission San Juan Bautista in the early 1800s, a missionary named Padre Felipe Arroyo de la Cuesta recorded a translation of over 3,000 Mutsun words. Study continued into the 20th century to include that of John Hartington, who continued to record more words and shared knowledge from one of the last fluent native speakers of the Mutsun, Ascension Solorsano, who passed away in 1930. You can share in some of her words as well other exhibits at the Chitactac-Adams Heritage County Park in Gilroy.

Chitactac village was at a junction of several Native American trails crossing through this valley. To the west, through the Santa Cruz mountains, the Amah Mutsun would share history with the Awaswas villages, the Tamyen villages of the north, and the various Mutsun villages to the east and south.

Today, visitors can come to the 4.5-acre Chitactac-Adams Heritage County Park and explore and learn about the people, plants, wildlife, and the ways of life by looking through their own historical windows into the past.

Portola Expeditions

Although all the land of California was inhabited by the Indigenous People, the territory was claimed by the Spanish Empire in 1542 by Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo under the Spanish flag. He discovered the Pacific Coast while trying to discover a route to Asia and the Spice Islands. On January 3, 1543, Cabrillo died somewhere near the Channel Islands after a fight with the Chumash.

In 1579, privateer Francis Drake was crossing the Pacific Ocean, following the trans-Pacific route which New Spain had mapped for trading from Mexico City to the Spanish East Indies. Drake ventured off and found land near Cape Mendocino (just south of Eureka). Francis Drake sailed south along the coast as far as Point Reyes, and while doing so claimed the land to be under English sovereign.

From 1595 to 1596, Sebastiao Rodrigues Soromenho, sailing under the Spanish flag, and under direct order of King Philip II, was ordered to map the coastline of California and identify maritime routes.

In 1602, Sebastian Vizcaino, under the Spanish flag, was tasked to not only to update the Soromenho maps, but also to determine strategic locations for future colonization, therefore establishing inland marches to include San Diego, the Channel Islands, and Monterey. It was nearly 160 years before Spain would once again have any interest of the lands north of Baja.

In 1759, Europe was in the middle of turmoil as the Suppression of the Society of Jesus had begun. As Europe was expelling the Jesuits from most of Western Europe, orders were eventually sent in 1767 to expel all Jesuits from the Spanish Empire. The Spanish crown began with reorganizing the viceroyalties, changing economic policies, and reorganizing the military. Word eventually made it to New Spain, and the order was given to expel the Jesuits within all of New Spain. There were 678 Jesuits expelled from the 16 missions and 32 stations within Mexico, 75% of them being Mexican-born.

Due to isolation of the various missions in Baja California, it was not until the newly appointed governor of Las Californias, Gaspar de Portola, arrived in 1767 that the Jesuits were removed from power and sent back to Europe. Portola then replaced the Jesuits with the Franciscans.

In the Spring of 1769, Portola launched two expeditions: one by sea and the other by land. The goal was to establish a military occupation of Alta California and establish routes from Baja to Monterey. This expedition became famously known as the Sacred Expedition. The first stop was San Diego, where they had to regroup, as two-thirds the maritime crew came down with scurvy and over half the Christianized Indigenous People deserted. Portola then reassessed the situation and adjusted the land expedition team down to a party of 64 persons, including Fathers Junipero Serra, Juan Crespi, and himself. They traveled north, trying to stay as close to the coast as possible. They finally reached Los Angeles in early August and then Santa Barbara by the end of the month. They continued north until they reached San Simeon. There, due to the high cliffs, they cut inland, and by the end of September reached the Salinas Valley. They followed the river and eventually ended up in Blanco (between Marina and Salinas) in early October, where they eventually spotted Monterey Bay. They never did find the exact spot described by Vizcaino. They traveled further north, trying to find signs of the ship San Jose, but never found it. They went as far as San Francisco but never saw it, so they realized that Monterey must have been the first harbor they spotted and went back. They surveyed the area and camped across from the Carmel River. Not seeing many people around, and with the weather turning and even snow on the hills, they erected a large wooden cross across the lagoon in Carmel and then headed back to Baja. Portola felt the expedition was a failure because they never found exactly what Vizcaino had described, but Serra and Crespi argued otherwise.

In April 1770, it was decided to build a mission and presidio in Monterey, so another expedition was sent. On this trip, Portola along with Crespi returned to Monterey and the cross left from the prior year. They took another look at the area and realized this had to be the spot Vizcaino described. It was then they started to build the mission and presidio in Monterey. Shortly after arrival in Monterey, Portola, Pedro Fages (deputy governor), and Crespi led an expedition back to the San Francisco Bay, but this time instead of using the route from the prior year through Santa Cruz, they went inland. They followed Indigenous trails and found an easier path through the Santa Clara Valley, thus passing right through where Gilroy is today. This is the first recorded time of a European presence in the area. This route would then be used as the preferred pathway to get from Monterey to San Francisco.

Important history to Gilroy starts on the 1769 Portola expedition. One of the Spanish soldiers who marched alongside Portola was Jose Francisco Ortega, who worked himself up to the rank of Sergeant. Ortega was appointed as lead scout on the 1769 expedition from the San Pedro Valley to locate San Francisco. Among his journaled discoveries was the locating of Angel Island, which he pointed out to Portola. The routes and journals he recorded led to the building of four presidios (San Diego, Monterey, San Francisco, and Santa Barbara). With all Ortega’s great accomplishments, Father Serra helped him to get promoted to the rank of Lieutenant and appointed as the Commandment of the Presidio of San Diego from 1773 to 1781, commandant of the Presidio of Monterey from 1787 to 1791, and eventually commandment of Presidio of Loreto from 1792 to 1795 before retiring as a captain with over 40 years of service. As part of Ortega’s retirement, governor Diego Borica gave him a Spanish land concession (the only land grant issued under the Spanish flag in California) consisting of six leagues, which he named Rancho Nuestra Senora del Refugio (today part of Santa Barbara County). Ortega went on to have 21 children (his sister had 22), one of which was Ygnacio Maria Ortega. He would himself receive one of the earliest land grants under Mexican rule of California called San Ysidro Rancho (roughly 13,000 acres to the east of Gilroy) around 1810. One of Ygnacio Maria Ortega’s sons-in-law would be John Gilroy, the individual for whom the City of Gilroy is named.

The Portola expeditions and the routes carved across the lands of California would be utilized and eventually link the California Missions together. Later in their lives, both Fathers Serra and Crespi discussed that there needed to be at least 10 to 11 missions built between Baja and San Francisco. They envisioned there should only be a maximum two to three days’ march between the missions. The chain linking the missions would serve as means of sharing food, resources, and the ability to send padres to help teach the Christian doctrine.

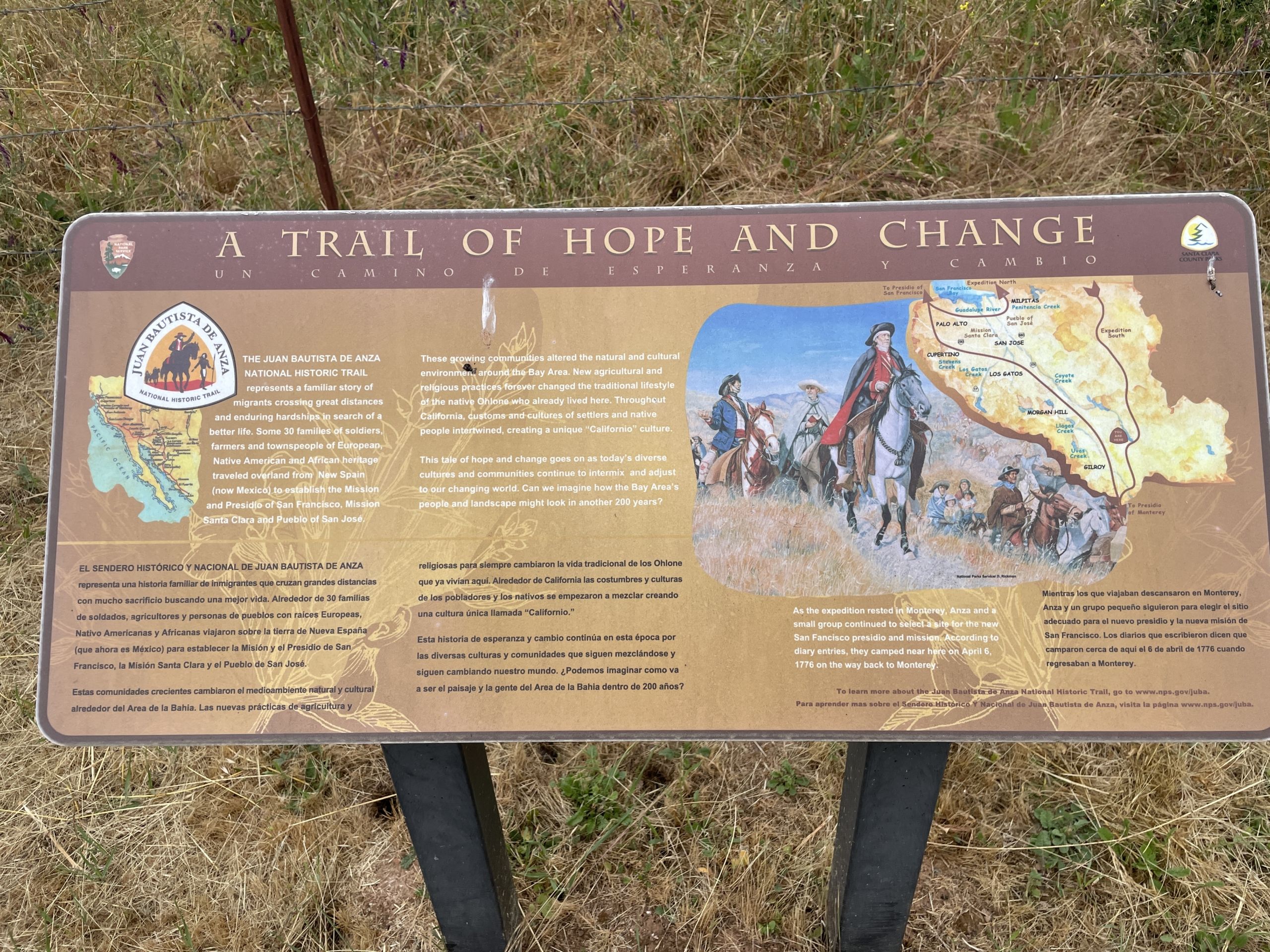

The Juan Bautista de Anza Trail

The commemorative Juan Bautista de Anza Trail extends for over 1,200 miles, stretching from near Sonora, Mexico, in a small town called Nogales, and extending to San Francisco, California. This trail commemorates the 1775-1776 land route that established a safe route from the Arizona territory to the California coast, which settlers would use in the ensuing years.

On January 8, 1774, Juan Bautista de Anza, along with 3 padres, 20 soldiers, 11 servants, 35 mules, 65 cattle and 140 horses, departed Nogales on a trip which would last 74 days. They crossed the Sonora desert and carefully travelled far enough south to avoid the Apache war parties. Eventually, they reached the Colorado River and traveled a short distance until they discovered what was to become known as the Yuma Crossing. It was shallow enough for them to safely cross over; otherwise, they would have had to travel across the treacherous Algodones Dunes.

The Algodones Dunes is an extremely large sand dune field with soft sand that would stop their carts—and as far as one’s eyes can see, the dunes are barren of everything including any form of life. The party followed the Colorado River south for about 50 miles to get around the south end of the Algodones Dunes and started a westward direction until they reached the present-day Mexicali. Here, they finally turned north into the present-day Imperial Valley. They then proceeded to cross the desert on the northwest side of the valley, then through the mountains, where on the other side they finally reached the coastal valleys of Southern California and arrived at the Mission San Gabriel Arcangel (located near Los Angeles).

After a short rest, de Anza gathered his party and started the return trip. This time he retraced his route and shortened it to exclude the days of exploration of various pathways of discovery. He used straight routes between friendly Indigenous villages he had discovered along the way. In total, the return trip took only 23 days. He mapped out a trail that showed a clear path from Tubac, Arizona to the California coast with plenty of resources and fresh water along the way.

On October 22, 1775, Juan Bautista de Anza started a second expedition, leaving Tubac, Arizona with over 240 friars, soldiers, colonists, 695 horses and 385 Texas Longhorn bulls and cows. The purpose of this expedition was to retrace his mapped route to Mission San Gabriel Arcangel and then head north following the routes established by Portola, Crespi and Serra to eventually make it to the San Francisco Bay, where they would establish the Presidio of San Francisco followed by the Mission San Francisco de Asis (aka Mission Dolores). The advanced party of the expedition reached San Franscisco on March 28, 1776. The main body of the expedition would reach the spot in the San Francisco area, where the advanced party planted a cross and letter declaring the land under Spanish control on June 27, 1776. The cattle and horses brought to California would be the grassroots of the cattle and horse industry in California, where the population of the two nearly doubled in size each ensuing two years.

The Anza Trail passes through Gilroy (in Henry W. Coe State Park) . In the diary of Franciscan missionary Fray Pedro Font (Anza’ s chaplain and geographer) on April 7, 1776, Font describes the party after attending Easter Services descending Coyote Creek past some hot springs and called the area “San Bernardino Valley.” These hot springs are today known as the Gilroy Hot Springs.

Another interesting story about how the De Anza expedition and the City of Gilroy cross paths is the story of one of the individuals in the party was Martina Ana Josepha de Castro. She became one of the earliest romances in California when she married Jose Maria Soberanes in Monterey, a scout form both the 1772 and 1776 Portola expeditions whose job was to discover mail routes. Martina and Jose’s second child was born in 1779, and another member of the Anza expedition named Apolinario Bernal would be the one to find the sick sailor from the Isaac Todd named John Gilroy one day in 1814. There they took John Gilroy to Rancho San Ysidro where he could be nursed back to health.

El Camino Real “The King’s Highway” or the “Royal Road”

El Camino Real was originally a continuation of the Baja California mission trail first established in 1769. This 600-mile commemorative route links the border of Mexico in San Diego traveling through California and ending in Sonoma. The first leg of the El Camino Real was created by General Gaspar de Portola on his 1769 expedition, traveling from San Diego to Monterey as they traveled along existing Indigenous Trails. The route was expanded upon by the Anza Trail. The overall trail was originally a footpath linking the 21 California Missions, four presidios, three pueblos and numerous submissions.

This trail was used in the 1800s by the Butterfield Stagecoach. In the mid-nineteenth century, several sections of the road were improved to accommodate larger stagecoaches and freight wagons. In 1915, the Automobile Club of Southern California traced the route, which soon became the route used by romantics to travel and see historic locations throughout California. In 1959, the state highways of Highway 1, U. S. Route 101, and Highway 82 were labeled as official highways of the El Camino Real.

A few miles from Gilroy in the town of San Juan Bautista, you will find the fifteenth mission in the chain. Here, behind the cemetery of the mission, you can visit an unsoiled section of the original El Camino Real.

Monterey Captured and Under Control of Pirate Hippolyte Bouchard

On September 16, 1810, armed conflict began in Dolores, Mexico, as a Roman priest named Miguel Hidalgo y Costillo rang his church bells signaling the call to arms. While this bloody and lengthy war lasted until 1821, life in the Bay Area was unaffected. Typically, there were only about two supply ships a year which sailed into Monterey carrying fresh provisions and news. In 1818, Monterey was attacked by two Argentinian ships captained by the privateer Hippolyte Bouchard. After four days of artillery attacks, Bouchard easily captured the presidio (occupied at the time with only 65 poorly trained and equipped men), the mission, and surrounding lands. He claimed Monterey under the Argentinian republic; but after ten days, his crews pillaged the town, set it on fire, and destroyed the cannons by partially burying them and firing them. They then boarded their ship and left, and the Presidio was rebuilt. Bouchard attacked a few of the missions, but mainly only those on the coast. When Mission San Juan Bautista heard news of the attack, they prepared themselves just in case, as the attacks on a sister mission were a few scant leagues away.

Mission San Juan Bautista and Surrounding Area

Even though the mission was founded and blessed by Father Lausen on June 24, 1797, this mission was a small adobe with thatch roof until June 1803, when the first cornerstone of the church was placed. The church was not completed until 1817. Thomas Doak, a sailor who jumped ship in Monterey, helped build the tile floors, painted the altar and reredos (altarpiece).

The local Ohlone tribe known as the Mutsun inhabited the surrounding area. The Mutsun were vital to the growth of the Mission as well the eventual surrounding area. The Mutsun population grew rapidly as they collectively came to the area and interacted with those working at the mission. The Mutsun assisted in the building of 128 adobe buildings along the El Camino Real. Today you can visit downtown San Juan Bautista and visit Plaza Historic District and see the only intact example of the traditional Spanish Mexican colonial architecture that dates between 1813 and 1870. One of the most famous of these buildings in this Spanish Plaza is the Plaza Hotel. This building was first constructed in 1792 as a house for Native American converts and laborers, then eventually became the barracks in 1813 for the Spanish soldiers.

Of the 128 adobe buildings built along the El Camino Real which stretches into “Old Gilroy,” a portion of those would be upon the land granted to Ygnacio Ortega in 1809. John Gilroy eventually found his way to this buildings and in 1821 married Clara Ortega (one of the daughters of Ygnacio Ortega). Ortega had used his rancho to create a large soap manufacturing business which employed John Gilroy. In 1833, Gilroy was awarded one third of Ortega’s land grant and used a portion of it to manage his industries of soap, onions, flour, and millstones, which he mainly traded with Monterey.

Mexican American War Passes through Rancho Ysidro

On December 27, 1845, U. S. President James Polk signed the annexation of admission of Texas as the 28th State in the Union. Tensions between Mexico and the United States were tense, and Mexico already failed to follow through on their threat to go to war if Texas became part of the United States. The recently elected President Polk had all eyes on “Manifest Destiny,” with goals of cutting tariffs, securing the Oregon Territory from Britian, and acquiring the territories of California and New Mexico from Mexico. Anticipating war with Mexico, Polk sent several naval vessels to protect U.S. ships sailing in the Pacific waters.

One of the U.S. Army forces posing as surveyors was led by Capt. John C. Fremont. Fremont spent time visiting all the American settlers and travelers in the area, speaking of news from Texas and what the U.S. was talking about with expansion of Manifest Destiny. All this excitement forced Mexican Governor Jose Castro to mark all land grants null for non-Mexican naturalized citizens. Anger and fear grew among the settlers within the Northern California area. On June 8, 1846, at the Old Moon Inn at Sutter’s Fort, a meeting was held to include the likes of a past resident of Rancho Ysidro named Nancy Kelsey. The next day, this band captured several horses and gave them to Capt. Fremont. A few days later, June 14, this band marched upon Sonoma and the home of General Vallejo and declared California an independent republic and no longer under Mexico’s authority. Word got out about this, and on July 1, Fremont took control of San Francisco, and Commodore John D. Sloat took control of Monterey.

After regrouping his forces, Capt. Fremont had received communication to sail down and take San Diego, where (with Commodore Stockton) he marched and took Los Angeles on August 13. Fremont returned to Monterey to gather more men and supplies, rode into Rancho San Ysidro, and proceeded to appropriate nearly all of John Gilroy’s horses. From here, he rode down to take control of Santa Barbara.

Butterfield Overland Mail Route (1857-1861)

As the United States expanded westward, the desire to have communications shortly followed all the settlers. With the growth in population with the Gold Rush starting in 1848, there was a high demand to have communications between the two coasts. At the time, the only way mail was able to get to California was by a boat sailing around South America. A letter from New York to San Francisco could take 150 days. If you were able to have a letter travel by carriage wagon, it could take 180 days. Therefore, in 1857, the United States Post Office sought a better and faster way of getting mail from New York to California. Congress quickly approved the awarding of a contract, and the award went to John Butterfield, Sr., and his Overland Mail Company. John Butterfield had been involved in the shipping business since the 1820s and eventually started his own livery business in 1827.

The contract identified five separate basic routes to be known as Divisions. The route which led to San Francisco was identified as the First Division. John Butterfield, Sr. then assigned the task of designing the exact route to his top two employees, Marquis L. Kenyon and John Butterfield, Jr. The contract spelled out they had a one-year goal to organize, finalize and identify the route for the First Division. On November 20, 1857, they departed New York by steamer ship and sailed to San Francisco.

On January 16, 1858, the two left San Francisco with pack mules and started traveling and identifying what would be the route and each of the stage stops leading across California. They headed east while another team left at the same time traveling from St. Louis headed west, with a goal of meeting each other in El Paso, Texas. The trip east from San Francisco to El Paso took 31 days, while the second westbound team took 21 days. After reviewing the preliminary route, Kenyon was not satisfied. They traveled a few sections again and remapped the route, identifying different stations. After this route was completed, Butterfield worked on the Second Division route while many others were tasked in improving conditions of the route: digging wells for drinking water, strengthening roadways, and even constructing a few bridges.

One significant decision for the route impacted the Gilroy community directly: the development of Pacheco Pass. Prior to 1856, the pathway which was the basis for the Pacheco Pass was a very narrow and windy single horse trail that wound from Bell Station to Gilroy and on the other side a carriage trail from Bell Station to San Luis Ranch. In 1856, Andrew Firebaugh recognized the opportunity to improve the route over to Gilroy for trade in Old Los Banos and surrounding areas. He organized and fixed the route and built a toll road from Gilroy to Bell Station to pay for the construction of a safe wagon road.

On September 16, 1858, at 6:00 p.m. the first stagecoach left Tipton, Missouri enroute to San Francisco. On board was Waterman L. Ormsby, a correspondent for the New York Herald who journaled the first-ever travel on the Butterfield Overland Stage, writing about all 53 stops for a feature article.

On this route there was a stop for fresh horses and water with a mail stop in Old Gilroy outside of a hotel located near Soap Lake (in present-day San Felipe). Ormsby journaled how skilled the drivers were riding quickly through the 12 miles winding down from Bell Station to Gilroy, where they were greeted by friendly and inquisitive citizens and enjoyed a nice dinner before climbing back in the stagecoach and heading to Morgan Hill, where the next stop was at the Seventeen Mile House. He described Gilroy having over 600 inhabitants, a number of fair houses, and several stores.

The Butterfield Overland Mail ran from September 1858 to March 1861 making two trips a week . The stages departed every Monday and Thursday from St. Louis and San Francisco. In 1861, due to rising debt, John Butterfield was voted out as President of his company. The postal contract was then awarded to Central Overland Trail and included the Pony Express. A large reason the contract changed hands was due to the impending start of the Civil War and the desire to ensure the mail contract stayed safely in Union hands. John Butterfield went on to be one of the founders of American Express. His son, Daniel, became a General in the Civil War and was awarded the Medal of Honor after he was wounded at Gaines’ Mill in the Seven Days Battle. While recovering from his wounds, he wrote several bugle calls, including Taps, a burial call.

The Railroad Comes to Gilroy

In 1854, Theodore Judah was pushing for the idea of a transcontinental railroad that would link the East Coast and the West Coast to allow a much quicker way for people to travel and would also move freight more quickly as well. Unfortunately, plans were stalled as disputes between the North and South were at an all-time high in the pre-Civil War Congress. Therefore, Judah came to California and built the state’s first railway. In 1857, Judah published a pamphlet to promote his idea again. This time, he attracted the attention of what came to be known as “the Big Four”: Sacramento businessmen Collis Huntington, Charles Crocker, Leland Stanford, and Mark Hopkins.

The Big Four went on to construct the western half of the railroad and became the owners of Southern Pacific Railroad Company, which was founded as a land holding company in 1865. With the Civil War beginning in 1861 and the southern opposition removed, in 1862 Congress approved federal support to build the railroad by providing $16,000 for every mile of track built on flat land and $48,000 per mile to cross mountains. This was the birth of the Union Pacific (headquartered in Omaha, Nebraska) and the Central Pacific (headquartered in Sacramento). Up to this point there had been dozens of very small, localized rail companies that lay down tracks starting as early as 1855. The Central Pacific started laying rails in 1863, building an 18-mile track linking Sacramento and Roseville. The Southern Pacific Railroad Company’s main approach to expanding routes was by acquiring properties and creating subsidiary companies—as well entirely fictious paper companies—to thwart opposition to the rapid growth of routes.

In 1859, the San Francisco & San Jose Railroad was incorporated. With much of the funding coming from the county government, tracks were laid between San Francisco and San Jose with depots built in Santa Clara and San Mateo. The Santa Clara depot was completed in late 1863 and became the state’s longest continuous operating depot until it closed in May 1997.

One of the first “paper companies” established by the Southern Pacific Railroad Company was the Santa Clara & Pajaro Valley Railroad Company in 1868. The goal of this railroad was to build the route connecting San Jose and Gilroy. Everyone saw through the charade; even the newspapers stated the project was being completed by the Southern Pacific Railroad Company. On March 13, 1869, the route was officially opened in Gilroy next to Monterey Street. The Santa Clara & Pajaro Valley Railroad ceased to exist, as it was merged into Southern Pacific Railroad Company in October 1870. Another smaller company called the California Southern Railroad Company was started in early 1870 to acquire land for the route between Gilroy and Pajaro as well as tracks to Hollister and possibly to the San Joaquin Valley. Instead, after the merger, Southern Pacific Railroad Company completed the route from Gilroy and Hollister by the end of 1870 and finally to Pajaro on November 27, 1871.

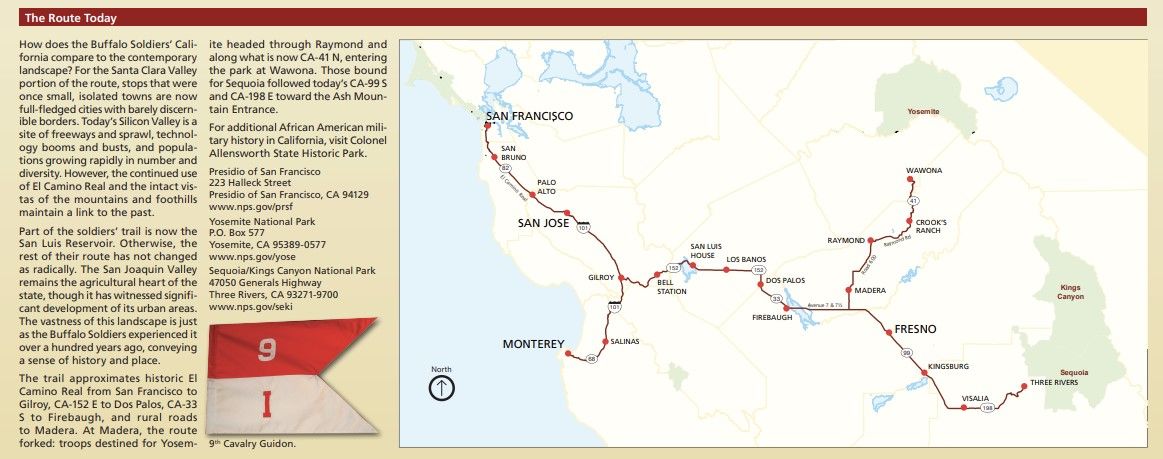

Buffalo Soldiers as Park Rangers

On August 25, 1916, Congress created a new agency under the U. S. Department of Interior called the National Park Service whose responsibility was to manage all national parks, most national monuments, and natural, historic, and recreational properties within the United States. The origin of the NPS started with a novel concept envisioned by George Catlin, an artist, after a trip to the Dakotas in 1832 where he felt there needed be a way to protect and preserve the beauty of our parks and lands before civilization destroyed them.

The first national park (created on March 1, 1872) was Yellowstone National Park. To protect the park and because of this area of Wyoming was still a territory and therefore had no state government, the United States Army was appointed to protect the lands. To protect the park and other national parks to come, portions of the 9th Calvary Regiment and the 24th Infantry Regiment were assigned.

In 1899, “Buffalo Soldiers” from Company H, 24th Inventory Regiment were assigned to serve and protect the Sierra Nevada and surrounding areas. They would leave San Francisco (or, starting in 1904, from Monterey) in May and returned from their round trip in November. The route would take them along the El Camino Real, marching through Gilroy as they headed east over the Pacheco Pass to get them to the Diablo Range before touring the San Joaquin Valley and the Sierra Nevada.

Birth of the Highways

On January 29, 1886, Carl Benz applied for a patent which became the birth of the automobile. Patent 37435 was for his Benz Patent Motorwagen, the first vehicle to have its own source of gas engine operation. In 1888, the first production began and started the automobile race. In June of 1896, Henry Ford created the Quadricycle, the first Ford car that was a wagon frame fitted with four bicycle wheels.

Before long, every American citizen wanted to own a powered engine vehicle. With automobiles on the rise, the first garage was opened in San Jose by Clarence Letcher, and one of the first automobile factories was opened called Osen & Hunt. As the desire for these automobiles was at an all-time high, clean flat roadways were needed to operate them upon. Dirt roads were turned into pebbled, then asphalt and concrete mix roadways. Single-lane and windy roads were straightened out and widened. Eventually, over time, some roads were illuminated with electric lighting.

Pacheco Pass (Highway 152)

On June 21, 1805, a son of one of the soldiers (Jose Joaquin Moraga) from the 1774 Juan Bautista de Anza Expedition who himself was a soldier and explorer named Gabriel Moraga discovered the pathway across the mountains and found his way to the San Joaquin Valley. Gabriel Moraga was appointed by his father to be the comisionado (military administrator) of the Pueblo of San Jose in 1777. In 1797, Moraga was transferred to the new town of Villa de Branciforte (part of modern-day Santa Cruz) while being replaced by Corporal Ignacio Vallejo (father of Mariano Vallejo). From 1806 to 1808, Moraga went on to discover, record and name several locations still known today such as the Sacramento River, Merced River, San Joaquin River, and Kings River to name a few.

During the 1820s and 1830s, this trail was used by Spanish and Mexican soldiers passing back and forth from Santa Clara Valley to the San Joaquin Valley. They were not the only individuals using this trail; so were the Indigenous People as they came from the various villages in the hillside to the San Joaquin Valley. They would enter the Santa Clara Valley and go on to Monterey as well to raid the missions, ranchos and various adobes for horses and cattle, taking them back to the San Joaquin Valley.

When word got out about the Gold Rush, this pathway was used extensively to bring materials, people, and more settlers to the area. Many people who failed at finding gold migrated down to the San Joaquin Valley to try there. Others simply relocated, and several crossed over to declare Santa Clara and Monterey Counties their new homes.

The west side was easy to navigate and reach the peak, as there was plenty of gentler grades allowing wagons to easily come from Gilroy up to what is known as Bell Station (originally known as Hollenbeck’s Station). On the east side, there was another story; however, the trail was narrow and at points wide enough only for a horse and wound down a rocky and steep grade. In 1857, Andrew Firebaugh saw an opportunity and hired several crew workers to develop a toll road from the Rancho San Luis Gonzaga to reach the Bell Station. From there, several folks were using the route daily going back and forth from valley to valley in less than two hours by wagon or mule train.

The naming of the route was due to the owner of the Rancho Ausaymas y San Felipe named Don Francisco Perez Pacheco. Francisco Perez Pacheco was born in Guadalajara, Mexico in 1790. In 1819, he migrated to Monterey, where he joined the Army at the Presidio of Monterey and was promoted to lieutenant after he led a successful revolt against the Mission La Purisima Concepcion. In 1827, Pacheco was elected to the Provincial Deputation for Alta California. Pacheco served proudly until 1846. While in his role, he spent his wealth and power to acquire various ranchos throughout California, one of which was the Rancho Ausaymas y San Felipe (over 35 acres) in 1833. The westward side of the entire route was on this rancho.

In 1915, the Pacheco Pass was formally incorporated into the state highway system and designated as Highway 152. On November 7, 1938, a contract was awarded to Granfield, Farrar & Carlin of San Francisco, sanctioned by the California Highways and Public Works to improve the route by realigning a section of roadway from Bell Station to Cape Horn as well turn it into a four-lane paved highway. The old highway was 3.46 miles, with a total curvature of 2,313 degrees (over 39 curves), maximum radius of 100 feet, and maximum grade of 7 percent. The new highway when completed was 2.63 miles, total curvature of 295 degrees (8), maximum radius of 850 feet, and maximum grade of 6 ½ percent. This project moved approximately 600,000 cubic yards of dirt and had two new concrete bridges added as well. This project added to the completed 1934 project working on a 3.3 mile stretch of road eastward of the Summit. In 1950, the four-lane project was completed for the 12-mile route. Since 1950, there have been several projects to improve the route to accommodate heavier trucks and improve safety.

Hecker Pass

Highway 152 splits as it crosses over Highway 101 within Gilroy’s city limits. The other side of Highway 152 is known today as Hecker Pass. Hecker Pass is a low mountain pass across the Santa Cruz Mountains that connects Gilroy to Watsonville. This roadway has a storied past, much as the other half of this highway, known as Pacheco Pass.

The origins of Hecker Pass were a series of Indigenous Trails connecting the Amah Mutsun tribes of the Santa Clara Valley with the Awaswas of Santa Cruz, Costanoan, Esselen and Salinan tribes of Monterey. In the mid-nineteenth century, as settlers and Gold Rush miners came south to settle into either Santa Cruz, Watsonville, or Gilroy area, timber was needed to build homes and businesses. This timber was locally sourced from the Santa Cruz mountains.

On the Gilroy side, George Homer Bodfish was one of these pioneers, as well as William Hanna, who created a sawmill and provided much of the timber used to construct the buildings for New Gilroy. George Bodfish and his brother Orlando started a lumber mill in the San Jose area. Eventually, they needed another source closer to Gilroy and south Santa Clara for operations here and for sale of lumber to pioneers in the San Benito County and Monterey County areas, even reaching out as far as San Joaquin Valley and hauling timber across Pacheco Pass. The Bodfish brothers purchased land in what was known as the French Redwoods. Using steam engine power, they were able to produce over 5,000 feet of timber a day.

Pathways led to dirt paths and roadways carving up into the Santa Cruz mountains hauling timber down to the mills. As the Gold Rush boomed, the sawmill and land were sold off to William Hanna as the Bodfish brothers moved onto other endeavors. The roadway leading from Gilroy up into the hills was known as Bodfish Canyon, and the road was Bodfish Mill Road (though for many known only as Mill Road). In the 1870s, Bodfish Mill Road connected with the roadways coming from Santa Cruz and Watsonville.

In 1875, the Cattle King Henry Miller fell so much in love with the scenic redwoods that he bought land near the summit of the Santa Cruz mountains and set up tents for camping. Every chance he got, he came back to rest and enjoy his land and eventually built five structures. The main building was a home where he and his family spent much downtime and hosted major BBQs for those all around the area.

Bodfish Road flourished and grew over the years. In the 1920s, with the growth of automobiles and the need for a roadway system, the birth of a plan called the “Yosemite-to-the-Sea Highway” was born. The vision was an easy-to-travel paved road system to get from Yosemite National Park to the ocean just south of Santa Cruz. The author of that plan was Henry Hecker, the nephew of famed Friedrich Hecker, a German lawyer, radical champion of popular rights for Algiers, newspaper publisher, defender of democracy for Baden (Prussia), part of the Illinois Republican Party with Abraham Lincoln, Colonel in the Union Army during the Civil War, and Fremont supporter. On May 27, 1928, the roadway officially opened and was named after its plan founder, becoming Hecker Pass.

Highway 101

The birth of U. S. Route 101, known today as Highway 101, was established as part of the United States Numbered Highway System in the 1920s. The highway’s design was to encompass a route from San Diego, California to Port Angeles, Washington with initial alignment to follow LRN 2 from San Francisco to San Diego. The final plan in 1926 changed the north ending route to the east side of the Olympic Peninsula to Olympic. The first section of US 101 completed was from San Diego to Los Angeles in 1928. The route in California was designed to incorporate most of the El Camino Real instead of LRN 2.

Splits and alignments were the norm with the growth and completion of the route. In 1951, just south of Gilroy to the San Benito County line, the roadway was widened to a four-lane expressway. In 1956, the three-lane width route from Ford Road and Llagas Creek was expanded to a four-lane section. In 1959, the California Highways & Public Works announced a study to be made for the route from San Jose through Gilroy to be upgraded to potential freeway.

In May 1961, the California Highways & Public Works announced the adoption of the freeway alignment, with a length of 24.6 miles between San Jose through Gilroy. US 101 was completed to freeway standards in Gilroy by 1972, moving US 101 away from Monterey Street onto what was known to locals as the freeway bypass (or Valley Freeway).